All times are UTC (Coordinated Universal Time) and all frequencies are in khz.

R adio Dap Loi Song Nui is the name of a station that broadcasts to Vietnam, which translates as Vietnam Democracy Radio. It broadcasts from 1230-1300 UTC on 9670 khz with 100 kW and transmits, of course, to Vietnam in Vietnamese.

adio Dap Loi Song Nui is the name of a station that broadcasts to Vietnam, which translates as Vietnam Democracy Radio. It broadcasts from 1230-1300 UTC on 9670 khz with 100 kW and transmits, of course, to Vietnam in Vietnamese.

Still in the region, Voice of Martyrs, via RRTM Telecom in Tashkent, also transmits from 1200-1230 UTC at 9929.9 khz with 100 kW in the Korean language with broadcasts destined for North Korea. This station also broadcasts from 2100-2130 UTC on 7530.khz with 100 kW in Korean.

Another interesting underground station is Dimite Wegahta Tigray which broadcasts to the complex Tigray region of Ethiopia. The Tigray region is currently experiencing a turbulent political situation, including armed conflicts with the central regime in Addis Ababa.

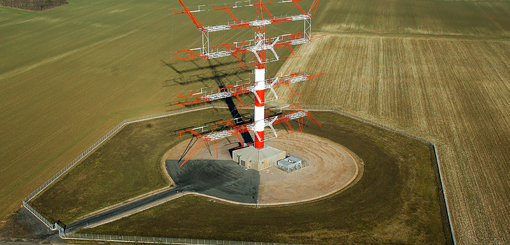

Dimite Wegahta Tigray transmits via TDF Issoudun, in France, from 1700-1800 UTC at 15340 khz with 250 kW in Tigrinya language.

Austria is still audible on shortwave, as the local public radio service: Oesterreichischer Rundfunk-1 can be heard from 0500 to 0620 UTC on 6155 khz, on the 49-metre band, with 300 kW in German language, exclusively from Monday to Friday. On weekends it is broadcast on the same frequency from; 0500-0610 UTC. It is interesting to note that this transmission is broadcast in German language and is directed to Central Europe.

Another country that can be picked up on shortwave is Canada. Although its international shortwave service is no longer aired, there is one private broadcaster that is still strongly committed to this type of transmission. This is CFRX from Toronto on 6070 kHz in English. From South America, we recommend trying to listen to it at about 05 UTC.

We return to the Asian continent. More precisely to the Middle East, as Radio Kuwait can be heard from 16 UTC in Arabic on the variable frequency of 15539.7 with 250 kW.

Another important piece of news that has happened in recent days takes us to Venezuela.

The head of Radio Rumbos, Elsa Siciliano, informed that the station's programming on 670 kHz FM is "suspended" until a problem between partners over the control of the station is clarified.

The board of Radio Rumbos said in a statement that the decision was taken to suspend programming after learning of the decision of the Constitutional Chamber of the TSJ (December 2020) ordering the closure of the plant and the eviction of the facilities. However, she pointed out later that the order was suspended by the same High Court.

The court order, dated 1 December 2020, includes the eviction of the station's facilities, but it is not known who will take over the management of the station.

They indicated that connections with the Rumbos Giant Circuit, whose 50 radio stations transmit daily Noti-Rumbos broadcasts, are also suspended.

We now turn to an interesting piece of information that involves the whole of Europe, as state-ran media outlets in several countries are under pressure from their respective governments, which are trying to strip them of their independence and turn them into their mouthpieces. Alarm bells are already ringing.

The pandemic has boosted the audiences of Europe's state media, with Europeans turning to fact-based news, according to media researchers.

All TV, radio and digital media channels have experienced audience increases, especially in Western Europe.

But while the public seems grateful, the continent's state broadcasters face a double threat. Governments in Central Europe have been or are seeking to reduce these stations’ editorial independence, transforming them into pro-government outlets, warn human rights activists and journalists.

In Western Europe, by contrast, centre-right governments are coming under increasing pressure from conservative and lawmakers to defund public broadcasters.

Attention in recent weeks has turned to Czech television and what critics of Prime Minister Andrej Babis' government say are efforts to politicise the broadcaster’s board and undermine its management team ahead of parliamentary elections in October.

Last week, the European Broadcasting Union (EBU), a trade association, urged Czech lawmakers to protect the independence of the country's state broadcaster, saying Ceska Televize is "the most widely watched news source in the Czech Republic, with 60% of the country using its services at least weekly".

EBU president Delphine Ernotte Cunci and the association's director general, Noel Curran, noted that they also "had the trust of more Czechs than any other news outlet". They based their claims on data and surveys compiled by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford University.

Last November, the broadcaster's supervisory board, which oversees operations, appoints the general director and approves the budget, was abruptly abolished. The country's parliament voted last week on a list of new board members, all affiliated with the ruling ANO party, which in Czech means Yes.

The broadcaster's current beleaguered director general, Petr Dvořák, told local media: "The aim is not to change one person in a leadership position, but to change the whole of Czech television, its behaviour and functioning".

He warned that the plan is to make the broadcaster appear formally independent, but it will be made to reflect the views of the ruling party. "The same thing has happened in Poland," he added. Dvořák expects to be removed from office soon.

Krzysztof Bobinski of the Polish Society of Journalists is concerned that public broadcasters in eleven EU member states are at high risk of coming under the control of the ruling parties.

Bobinski urged the European Commission, the Council of Europe and the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe to work more closely together to highlight how "too many EU governments are using state media to skew public debate in their favour and thereby threaten the quality of democratic processes and the rule of law".

Babis' moves to change state broadcasting in the Czech Republic are mirroring actions elsewhere in the young democracies of Central Europe. After he won power, Poland's Law and Justice Party clipped the wings of the country's public network, TVP.

The OSCE observation mission to Poland's 2019 parliamentary elections noted in its report a "lack of media impartiality", especially in TVP's coverage.

Reporters Without Borders says Poland's state media "have been transformed into propaganda instruments". The group has expressed similar concerns about public media in Hungary. During the country's 2019 elections, leaked audio recordings emerged of editors instructing reporters to favour Viktor Orban's ruling Fidesz party in their coverage.

Populist leaders say the criticism is unfair and that public broadcasters have been mouthpieces for liberals and the left for years. Slovenia's prime minister, Janez Jansa, accuses his country's public media of regularly spreading "fake news".

He has called the Slovenian Press Agency a "national disgrace" and says reporters working for the public broadcaster Radiotelevizija Slovenija are paid too high a salary and spread "lies". His government wants to amend the country's media laws so that it can increase state influence over public service media.

Central European populists' criticism of public broadcasters echoes Western European counterparts, who identify public media as liberal and accuse them of being hostile to them, and dominated by a metropolitan mentality out of tune with the lives and thinking of millions of what they describe as “ordinary Europeans”, especially those living in rural and non-industrialised areas.

Germany's populist Alternative for Germany (AfD) party has been engaged in a war of words for years with the country's state broadcasters. In 2017, it went to court to try to win more airtime for its representatives, accusing broadcasters of routinely discriminating against them.

Executives at German public service broadcaster ZDF have admitted that they have often focused too much on covering issues and events in the country's large metropolitan areas and have not provided enough coverage of the rural east. They say this is something they are seeking to rectify.

In the UK, the Conservatives in government have long had a tense and ambivalent relationship with the BBC, which they accuse of liberal bias. In addition, libertarians are opposed in principle to the use of public funds.

The BBC is largely funded by an annual television licence fee charged to all British households, businesses and organisations that use any equipment to receive or record live television broadcasts and catch up with iPlayer.

The Conservatives pledged in 2019 to reform the BBC and review its funding. There has been a growing movement in recent years to abolish licence fees, and a growing number of Britons have outright refused to pay them.

"There is no need for the BBC," according to Alex Deane, a public relations consultant and former adviser to the Conservative government. He says resentment towards the BBC is not based on right or left wing politics, but is rooted in "cultural issues and issues like Brexit and patriotism". And he says that in the digital age there are many commercial sources of news and entertainment.

But the BBC's defenders say it is respected both in Britain and around the world for its reliability, the strength of its journalism and its impartiality, and point out how in times of crisis it is the preferred news source for Britons over its commercial rivals.

Ninety-three per cent of the British population tuned in to BBC television or radio during the first two weeks of the 2003 war in Iraq, according to polls. At the start of the pandemic in March 2020, when Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced the start of tough new restrictions on the coronavirus, more than 15 million viewers watched BBC coverage, twice as many as turned to commercial rivals.